Henry Brandts-Giesen – Originally published at Dentons Kensington Swan

![]()

The greatest transfer of wealth in modern history is underway. Families that are unprepared for this transition of value and power expose themselves to risks that can compromise decades of enterprise and hard work. In the author’s experience informal family governance structures that once might have been appropriate may now need review and reform to ensure they are fit for a future where traditional leaders have less influence and the family may have more wealth consumers than generators.

Developing a family charter (also known as a family constitution) can be an important part of this process. The following paragraphs will attempt to define a family charter, explain how it may benefit a family, provide some suggestions on the consultation process that should precede the drafting of a family charter, and give some examples of the types of matters that a family charter might address.

What is a family charter?

A family charter is a written statement that serves as a record of a family’s heritage, culture, hopes, and ambitions for future success, as well as a plan for the future. At its core will be the mission statement for the family and some clearly stated aspirations for current and future generations.

A family charter will also typically set out broad principles around the governance, management, and use of family assets and profits. It may include specific policies on matters such as investment, education, the family business, and conflict resolution.

Why have a family charter?

A family charter can be the centerpiece of a framework that engages family members with the business, legal structures, and advisers. It can provide for family members to play a role in the governance of the family’s properties, affairs, and interests if that is desired. Alternatively, family members can step back and focus on their own careers in reliance on robust structures and procedures set out in the family charter and corresponding legal documents. This can help the family avoid disharmony and disputes or other adversities that can be harmful to the family mission.

Family charters can also provide a degree of flexibility in arrangements for families and can be amended to reflect changes in relationships, strategic asset allocation profiles, and other circumstances. A family charter should be a living document that is reviewed regularly and evolves over time in a manner that is not always possible with certain legal documents (such as trust deeds and shareholder agreements).

Dispute resolution mechanisms are often included in a family charter. Experiences of families who have gone through the process of creating a family charter suggest that disputes can be less severe, and in some cases be averted altogether by the activation of those mechanisms.

The ten domains of family wealth

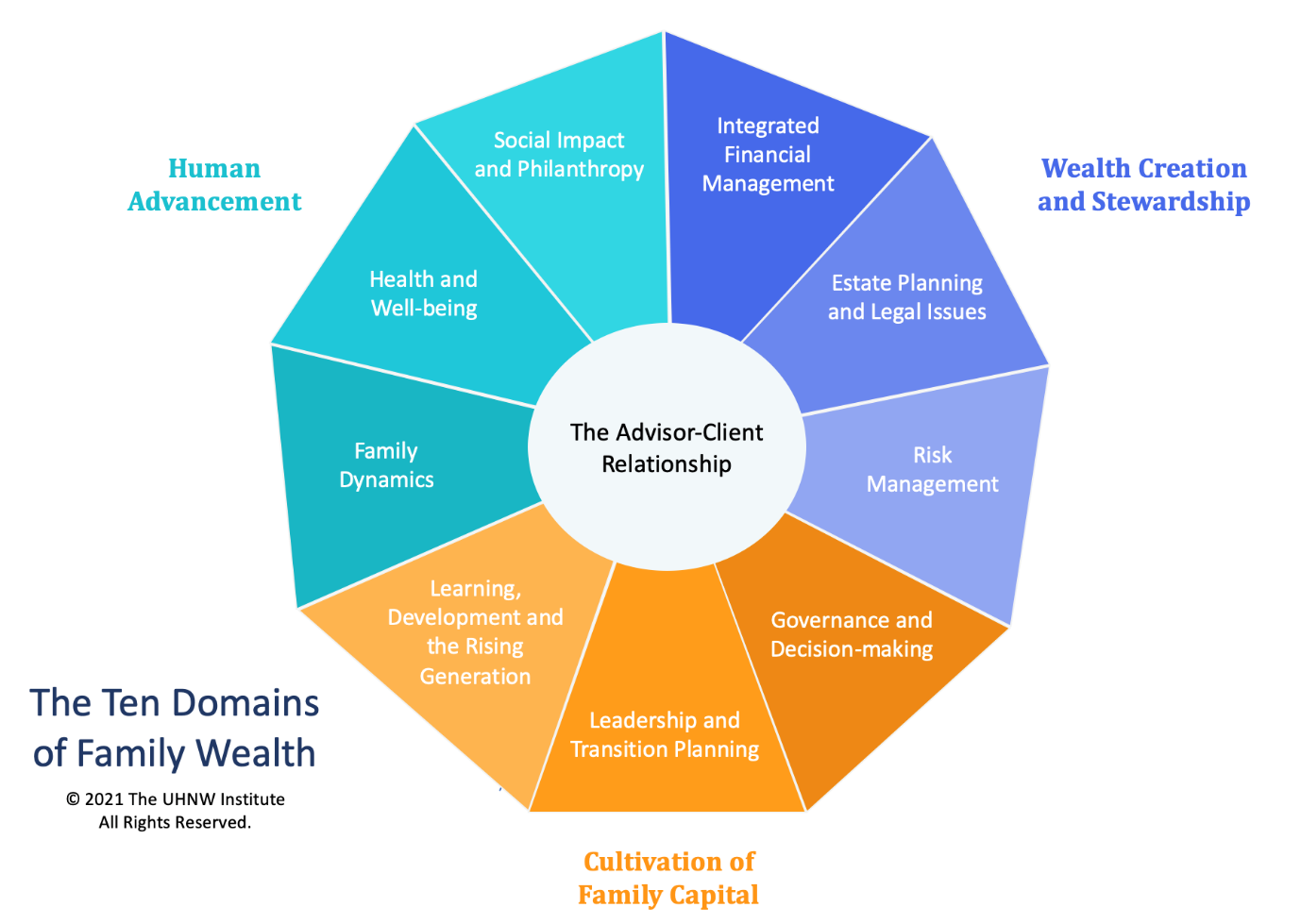

A new paradigm has been developed by the UHNW Institute and may be transformative for families, their advisors, and the wealth management industry. The Ten Domains of Family Wealth extolls the benefits of a comprehensive understanding of family wealth and pulls together the many and varied services needed to integrate a family’s financial, social, cultural, and emotional capital. By adhering to this model families and advisors are encouraged to move beyond professional boundaries and organize themselves better to deliver services in an integrated, cohesive, and holistic manner.[1]

The Ten Domains of Family Wealth comprise one central organizational domain focussed on coordinating the delivery of specialist services within nine technical domains.[2]

The advisor-client relationship is central to the paradigm as it unifies and coordinates three specialty areas each comprising three sub-specialisations:

- Wealth creation and stewardship

-

- Integrated financial management

- Estate planning and legal issues

- Risk management

- Cultivation of family capital

-

- Governance and decision making

- Leadership and transition planning

- Learning, development and the rising generation

- Human advancement

-

- Family dynamics

- Health and wellbeing

- Social impact and philanthropy

A central tenet of The Ten Domains of Family Wealth is that no single advisor is required (or even capable) to fulfil all the deeds in all domains for families. The domains simply represent the full landscape of what families need and what their advisors should be able to deliver, either in-house, on referral, or in collaboration with others in an open architecture environment that is free of siloed thinking, professional rivalries, and conflicts of interests/duties.

The concepts underpinning The Ten Domains of Family Wealth are sound but capable implementation is a major challenge. It is in this regard that a family charter can be of critical importance as it provides a road map and rules of engagement, not only for the family but also the advisors and service providers.

Distinguishing between advice and governance

A feature of some family holding structures can be a lack of independent governance leading to insufficient systems and processes to support the structure and assets held. This issue is especially acute in structures that hold first generational wealth and/or in jurisdictions that do not have a history of inter-generational wealth aggregation and an experienced advisory and regulated fiduciary services sector. Whilst independent governance may not be necessary during the wealth creation phase in the author’s experience it is an important ingredient for inter-generational wealth planning.

Some advisors to families conflate the provision of two very distinct functions: professional advice and governance. Advice and governance require different skills and have duties which are owed to different classes of people. A problem with this is that advisors can become conflicted by a long-standing relationship with the people who set up the structures and unable to properly fulfil fiduciary duties to the wider family. In some cases these advisors over reach their capabilities and do not have all the specialist skills necessary to advise the family. This can cause significant issues which are amplified where the advisor is also entrenched in a governance role within the family holding structure (for example, as a trustee or director of an operating company).

A family charter can be used to define the various roles and functions necessary to create, preserve, enhance, and transition family wealth across generations. A family charter can be a directory of the key advisors and stewards of the family wealth and provide some reassurance and clarity of their role (without entrenching them) in the family eco-system.

A family charter can also prescribe some principles and criteria for who may hold advisory and governance roles in the future (including maintaining a balance between family and independent representation).

A new form of capitalism – purpose over profits

Another reason for having a family charter is that as the business world cautiously navigates the medical, social, and economic consequences of the pandemic, there is a gradual realisation in some families that capitalism in its current form is causing as many issues as it purports to resolve.

Increasingly the “purpose” of a family and its business is being discussed in boardrooms and family meetings where previously profit was the most important agenda item. This means prioritising social responsibility, climate change, sustainability, diversity, economic empowerment, empathy, learning, compassion, and community engagement are new pillars for innovation and growth.

Progressive families and their businesses are adopting policies and procedures which encourage giving more than taking, choosing the future over the present, and public good over self-enrichment.

These values are not easily embedded into legal documents but can be embodied in a family charter.

Procedural steps towards developing a family charter

A family charter should be a bespoke document, not a standard form prepared by external advisers without intrinsic knowledge and understanding of the family dynamic and core values. The most important feature of the family charter is that it should be the embodiment of the personal ethos, and closely held principles, which the family members all agree between themselves to abide by when dealing with family wealth.

In author’s experience, the best outcomes:

- occur when discussions begin well in advance of any common trigger events (such as the death or incapacity of a family leader or the sale of a family property or business or other liquidity event);

- require an in-depth understanding of the family dynamics drawn from considerable time and effort in understanding and meticulously documenting all the relevant circumstances;

- involve engagement with all stakeholders, including family members and management of family owned businesses; and

- are often led by professionals trained and experienced in the science of human behaviour (such as psychologists) – rather than lawyers and accountants.

Engagement with the wider family

In many case the family leader initiates the process of creating a family charter with the help of an external adviser or facilitator. However, the depth and quality of the engagement with the wider family is usually what differentiates a successful outcome from those were the results are less impactful.

In less successful cases, family members are informed about the purpose of the charter and what it contains and are asked to review and comment on the document before it is finalised. In such cases discussion among family members can be superficial and avoids tensions or controversies. In the successful cases, family members have deep, meaningful, respectful but candid and robust conversations with the benefit of full disclosure of all relevant business information.

That is not to diminish the critical importance and even primacy of the views and vision of the wealth creators or current stewards of the family wealth, but rather suggests that at least in some families a command and control structure is not always appropriate.

It has been suggested by recognised experts that there are several keys areas of inquiry that families should pursue during this process:[3]

Do the family members want to stay together as a wealth collective?

Follow up questions:

- What do the family members want to do?

- What do the family members see as the benefits and challenges of shared wealth ownership?

- Do the family members acknowledge that staying together as a wealth collective means committing to loyalty and mutual support for each other?

- Will the family members identify shared values and shared culture that they intend to live by, preserve and pass on to the next generation through stories and rituals?

- What will be the benefits and challenges of working together?

- What does ‘working together’ mean?

- Do the family members enjoy working together?

- Will working together strengthen or weaken their bonds of affection for each other?

- Who wants to work with whom, and why?

- If one or more of the family members prefers not to work with other family members but wants to remain part of the wealth collective, how do we deal with that situation?

Do the family members want to create wealth and emotional attachment by working together?

Follow up questions:

- How will this happen?

- How do the family members make decisions concerning key issues such as leadership, governance, structures, policies, practices and succession planning?

- How do the family members deal with potentially sensitive issues?

In order to create wealth and emotional attachment, what do the family members do jointly?

Follow up questions:

- What do the family members do independently?

- What is each family member’s opinion of the industries in which the wealth collective operates?

- Who in the family would be involved in decisions about investing in or exiting from the wealth collective?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of owning joint assets?

- Are legacy assets protected and not to be divested?

- Should other assets also be protected?

- What estate planning issues might arise if a family member has no descendants?

- How high of a priority should the family place on minimising taxes?

- Does anyone in the family have an estate that is difficult to divide because it is illiquid or for other reasons?

- How do the family members address this challenge?

- Should the family use venture capital to encourage entrepreneurship in the next generation?

- How do the family members accommodate different needs, different views on risk and liquidity, and different stages of life (wealth accumulation phase versus wealth distribution phase)?

- How would the family address a family member wanting to exit from the wealth collective?

Does every family member feel that they are getting a fair share?

Follow up questions:

- What would the family members do if they have an underperforming asset whose future viability is uncertain?

- What are the options for family members who feel they receive economic rewards but have no emotional attachment to the wealth collective, or vice versa?

- What can the family members do to manage conflict or frustration or to address a perception of unfairness?

- If one or more of the family members are not getting sufficient economic rewards or benefits in terms of economic or socioemotional wealth, why should they continue as business partners?

- Should the family members conduct an annual family survey?

It takes months or even years for these conversations to take place between family members. In the author’s experience a collaborative team approach which brings together different advisors with different skills coming together as a team with the shared goals of assisting in the stewardship of the family and the protection of their assets. However, it is important that the family leader does not dominate the proceedings and that the advisors do not become servile. In some situations they may need to challenge family members in the interests of the wider family.

Form and content of a family charter

The content of a family charter will emerge organically as members of the family, business and trustees engage in dialogue with the advisers.

Some of the matters that are commonly addressed in a family charter include:

- Family statement (including mission, purpose, ethos, and values);

- history of the family;

- family tree;

- structure chart (including trusts, companies, limited partnerships, and charities, and a directory of key people involved in their governance and management);

- assessment of relevant risks;

- summary of strategic assets;

- family leadership structure and processes:

- decision-making protocols;

- committee or board structure; and

- allocation of power and responsibility;

- family business structure and processes:

- shareholder agreement;

- management and board appointments;

- independent (non-family) representation;

- share ownership (including arrangements for buying and selling shares);

- voting;

- advisory board;

- retained earnings / working capital; and

- dividend policy.

- employment policies for family members in the family business:

- remuneration;

- employment criteria; and

- career progression (KPIs, etc).

- profit distribution policy;

- statement of investment policies and procedures:

- strategic asset allocation;

- risk tolerance; and

- return profile.

- information sharing and reporting protocols;

- mechanisms to deal with disposals and transfers of interests in the family wealth;

- dispute resolution procedures;

- conflicts of interest;

- contingency plans:

- disaster recovery (pandemic, natural disaster, etc);

- illness, incapacity, or death of key persons; and

- insurance (captive, private placement, or traditional).

- media policies;

- succession planning;

- family meetings;

- family code of conduct:

- ethics;

- drugs, alcohol, tobacco, gambling, and environment;

- behavior towards each other that reflects the family’s values;

- meeting procedures;

- celebrating success;

- decision making; and

- directory of external advisers (including legal, tax, accounting, investment, etc);

- annexures (including copies of key documents such as trust deeds, shareholders’ agreements, and business plans).

A set of guiding principles – not rules

In the author’s experience, one of the fundamental mistakes made in family charters is the failure by inexperienced advisors to distinguish between rules and principles. Family charters should normally contain principles not rules. If they do contain rules then they should not duplicate, complicate or contradict rules in other documents such as trust deeds or shareholder agreements.

In this context a principle should internally motivate a family to do or refrain from doing something and in a particular way. A rule, however, should externally compel the family to do the things someone else has deemed good or right and has a consequence. Rules control processes and outcomes but principles guide them. Rules are contained in trust deeds, wills, shareholders’ agreements, contracts and the general law. Principles should be contained in family charters and letters of wishes. Documents containing binding rules should be identified and recognised but not usurped by the family charter. Instead, the family charter should seek to deal with situations in the governing documents of the family and/or its business where there are no rules or there are rules but they require some interpretation and the exercise of judgement (e.g. discretionary powers under trusts).

Conclusion

A family charter will not be essential or even helpful in all situations. However, in the author’s experience it can be an important document in a suite of systems, processes, structures, and documents that collectively can preserve and enhance family wealth and harmony. One reason for this is that informal governance structures are proving to be inadequate for families with significant wealth who are preparing to transition between the generations. Without forward planning a vacuum of power, value, and control inevitably arises on the death or incapacity of the family leaders and this often leads to conflict.

While often this issue can be dealt with in estate planning documents and shareholders’ agreements these are fundamentally legalistic documents and they may not resonate with (or even be properly understood by) all members of the family. A family charter can be a more humanistic and relatable document intended to create family cohesion and a sense of direction behind a collective purpose.

A family charter is, however, a unique and bespoke document. There is no template and deep and meaningful engagement with the family members is essential and, to some extent, the process is just as important as the outcome.